Precise dating of the pharaohs (kings) of Egypt is very difficult.

Before the coming of the Israelite kings whose reigns are reliably dated in the annals of Assyria (i.e. in the period before 853BC), assigning precise dates to particular people or events in the Old Testament is fraught with difficulties. A round-topped stone stela, which can be seen in the British Museum in London, records King Ahab of Israel and King Adad-idri (Ben-Hadad) of Aram taking part in a joint venture against King Shalmaneser III of Assyria at the Battle of Karkar in 853BC. This date is the earliest Old Testament date that can be corroborated from a non-Biblical source. Any date before 853BC is uncertain and may be hotly disputed.

Statue of King Shalmaneser III of Assyria

at the Istanbul Museum ( Bjørn Christian Tørrissen )

A further problem arises when trying to harmonise events that affected both Israel and Egypt. This is because a number of Egyptian pharaohs mentioned in the Old Testament are not named in the text. In order to identify these pharaohs, Biblical scholars have tended to rely on the dates traditionally assigned to the Egyptian pharaohs by archaeologists in the nineteenth century.

Unfortunately, however, the traditional dating method created over a hundred and fifty years ago is based on very flimsy evidence, and has been shown by contemporary archaeologists (such as Peter James in his book Centuries of Darkness and David Rohl in his book A Test of Time) to contain serious mistakes and inaccuracies.

In particular, the dates traditionally assigned to the pharaohs of the 21st and 22nd dynasties are grossly inaccurate. Traditionally, the years of each individual pharaoh’s reign have been added up and the combined totals projected backwards into history to determine the dates of earlier dynasties.

But it is now widely acknowledged that many of these pharaohs were rival pharaohs reigning at the same time in different parts of Egypt. Some of them also spent part of their reign as ‘regents’ or co-rulers while their fathers were still ruling. As a result, it is highly likely that - by adding these reigns 'end-to-end' - the traditional dating system has artificially extended the length of the 21st and 22nd dynasties by up to around 300 years, and has resulted in earlier pharaohs and dynasties being dated two or three hundred years too far back in history.

This 200-300 year inaccuracy in the traditional (Victorian) dating system is absolutely crucial when trying to identify un-named pharaohs in the Old Testament.

Ramesses II

Traditionally, the Pharaoh of the Exodus is identified as the 19th dynasty Pharaoh Ramesses II because the Hebrew slaves were forced to build the Egyptian store-city named in the Bible as Raamses or Ramesses and associated therefore with the great Egyptian city builder, Ramesses II (see Exodus 1:11). This traditional identification, however, does not take into account more recent archaoeological evidence uncovered since the 1970s which shows clearly that it was the earlier city of Avaris, built on the same site as the later city of Ramesses, that was constructed by the Hebrew slaves in the Bible.

It follows that the city referred to in the Bible as Raamses had an earlier name, and the Hebrew writer was either unaware of this or simply referred to the city using the name by which it was known at the time he wrote. In the same way, an English writer might refer today to the early history of London, Chester or Bath, not to the history of Londinium, Deva or Aquae Sulis, as most contemporary readers would be unaware of the earlier names of these cities.

The reign of Ramesses II, using the nineteenth century dating system, is traditionally dated as 1279 – 1213BC, and events once thought to be within his reign, including the Exodus, are therefore traditionally dated during this period. This, however, does not correspond to the dates suggested in the Old Testament where Solomon’s Temple (reliably known to have been built between 967/968BC and 961/960BC), is said to have been started 480 years after the Exodus from Egypt (see 1 Kings 6:1). This would place the Exodus in 1447 BC, 168 years before the ‘traditional’ start of Ramesses’s reign. Similarly, Jephthah (who ‘judged’ Israel from 1108 – 1102BC) told the King of the Amorites that it was 300 years since the Israelites occupied Moab (see Judges 11:26). Taking into account the additional forty years that the Israelites spent in the desert after leaving Egypt, this dates the Exodus to between 1448 and 1442BC. If the Bible text is accurate here, Ramesses II could not possibly be the Pharaoh of the Exodus – it must have been a much earlier pharaoh.

The ‘New Chronology’ proposed by David Rohl and like-minded archaeologists (and hotly disputed by others, who often reject the Biblical accounts as fictional) suggests that Ramesses II became pharaoh towards the end of the reign of King Solomon (971-931BC) and fought the Battle of Kadesh against the Hittites in 939BC. This battle is ‘traditionally’ dated as 1274BC, some 335 years earlier.

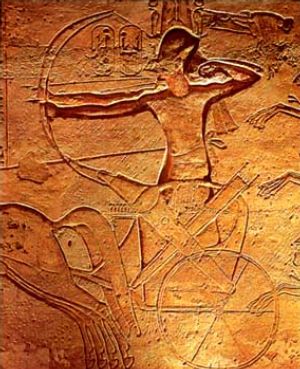

Ramesses II at Kadesh - relief at Abu Simbel

'Shishak' and Shoshenk

During the reign of Solomon’s son, King Rehoboam of Judah, the Old Testament records that Pharaoh ‘Shishak’ attacked Jerusalem, sacked the city and took away all its treasures (see 1 Kings 14:25-26). There is no pharaoh with the name ‘Shishak’ according to Egyptian records. Traditionally, ‘Shishak’ was thought to be Pharaoh Shoshenk I, as it was discovered in 1828 that an inscription at Karnak referred to a military campaign in Palestine by Shoshenk I. More recent scrutiny of this inscription, however, has shown that it does not mention Jerusalem. While Shoshenk campaigned in the northern part of Israel, the inscriptions do not suggest any attack on Jerusalem to the south in neighbouring Judah.

The ‘New Chronology’ attributes this attack on Jerusalem in 927 BC to Pharaoh Ramesses II of Egypt, who marched north to sack the capital of Judaea – the enemy of his ally, Israel. Indeed, an inscription at Ramesses II’s mortuary temple in Thebes records that he plundered Shalem in the eighth year of his reign. Shalem or ‘Salem’ is, of course, an earlier name for Jerusalem (Hebrew, Yerushalim) (see Genesis 14:18). The name ‘Shishak’ may simply be a representation of a shortened form of the name ‘Ramesses’ - ‘SS’ or ‘SySa’ - translated into Hebrew as ‘Shysha’ or ‘Shyshak’, meaning ‘the plunderer’, and written in English as ‘Shishak’.

According to the dating of the ‘New Chronology’, Pharaoh Shoshenk was, in fact, the unnamed ‘saviour’ of the Jewish people who repelled the Arameans (Syrians) when they attacked the north of Israel over a hundred years later, in 802BC (see 2 Kings 13:5).

Pharaoh Shoshenk's victory list at Karnak Temple

Akhenaten and Haremheb

If the dates of the Egyptian pharaohs as suggested in the ‘New Chronology’ are correct, King Saul and King David were able to extend the territories and influence of Israel around 1000BC because the pharaoh who ruled at this time, Akhenaten, was regarded as a religious heretic by his own people. He was therefore much weaker, militarily, than his predecessors, and was unable to support his allies, the Philistines, when they were attacked and defeated by King David. Indeed, many of the ‘Amarna letters’, written by Egypt’s Philistine and Canaanite allies to Pharaoh Akhenaten, at his capital in Amarna, request the pharaoh’s military assistance in dealing with the ‘Habiru’ (Hebrew) warriors who were threatening to overpower them at this time.

David’s son, Solomon, consolidated the extended kingdom of Israel by making peace with Egypt and forged a successful alliance by marrying Pharaoh Haremheb’s daughter in c.970BC. Egypt’s new ally, Israel was able to take over the ‘policing’ of the main coastal trade route from Egypt to Mesopotamia (the Via Maris) from Egypt’s previous ally, the Philistines. Solomon procured iron chariots from Egypt to patrol the coastal plain from his new chariot city at Gezer, given to him as a wedding present by the Egyptian pharaoh (see 1 Kings 9:16 & 10:26-29).

Statue of Pharaoh Akhenaten at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (Hajor)

Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV and Dudimose

If Ramesees II, traditionally associated with the Israelites’ flight from Egypt, was not the Pharaoh of the Exodus, then who was? According to the ‘New Chronology’, Moses was brought up as an Egyptian prince during the reign of Pharaoh Khaneferre Sobekhotep IV, and probably served as a young man in the pharaoh’s army that defended Egypt from its Kushite neighbours in c.1506BC. As an old man, Moses returned to Egypt to lead the Israelites to the ‘promised land’ of Canaan. The pharaoh at the time of the Exodus in c.1447BC was probably Pharaoh Dudimose, during whose reign the Egyptian city of Avaris was abandoned (after the Hebrew slaves left), before being re-built on the same site by Pharaoh Ramesses II over two hundred years later.

Amenemhat III and Neferhotep I

The Old Testament says that the Israelites spent 430 years in Egypt before the Exodus (see Exodus 12:40). However, the Jewish historian Josephus, says that this 430 years refers to the whole of the time since Abraham journeyed from Mesopotamia to Egypt (see Genesis 12:1-20), and it was only 215 years (half this time) between Jacob and his family moving to Egypt (see Genesis 47:11) and the Exodus. Bearing this in mind, the pharaoh who made Joseph the Vizier of Egypt was probably Amenemhat III, the most powerful pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom. The ‘pharaoh who did not know Joseph’ and who increased the burden on the Hebrew slaves (see Exodus 1:8) was probably Neferhotep I, who came to the throne some 70 years after Joseph’s death.

Pharaoh Amenemhet III (State Museum Munich) (Manfred Werner)

Nebkaure Khety IV

The further back in time we go, the less certain precise dating becomes. If, in accordance with the ‘New Chronology’, we are correct in stating that Abraham and Sarah moved to Egypt during the drought in c.1853BC (see Genesis 12:10-20), then the ruler at that time was probably Pharaoh Nebkaure Khety IV.